As AfCTA belatedly prepares to come into effect, GOLDSTREET BUSINESS, reproduces an econometric modeling – based report, released a fortnight ago by the World Bank Group and Proshare Economy, which presents quantitative forecasts on how the impending pan-continental single market will affect the Africa’s economy, its member countries and trade relations with the rest of the world.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement will create the largest free trade area in the world measured by the number of countries participating. The pact connects 1.3 billion people across 55 countries with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) valued at US$3.4 trillion. It has the potential to lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty, but achieving its full potential will depend on putting in place significant policy reforms and trade facilitation measures. As the global economy is in turmoil due to the COVID-19 pandemic, creation of the vast AfCFTA regional market is a major opportunity to help African countries diversify their exports, accelerate growth, and attract foreign direct investment.

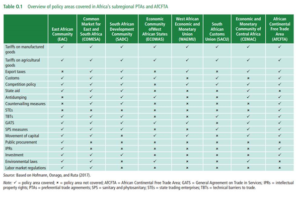

The scope of AfCFTA is large. The agreement will reduce tariff s among member countries and cover policy areas such as trade facilitation and services, as well as regulatory measures such as sanitary standards and technical barriers to trade. It will complement existing sub-regional economic communities and trade agreements in Africa by offering a continent-wide regulatory framework and by regulating policy areas-such as investment and intellectual property rights protection (table O.1)-that so far have not been covered in most sub-regional agreements in Africa.

Scope

To date, studies on the economic implications of Africa’s regional integration have mainly focused on tariff and nontariff barriers (NTBs) in goods. This analysis extends those studies to cover NTBs in services and trade facilitation measures. Most important, the analysis is extended to investigate the implications of AfCFTA for poverty, impacts on unskilled workers, and women.

In line with ongoing negotiations, the model assumes reductions in tariff and nontariff barriers and in trade facilitation bottlenecks. Specifically:

- Tariffs on intra-continental trade are reduced progressively in line with AfCFTA modalities. Starting in 2020, tariffs on 90 percent of tariff lines will be eliminated over a 5-year period (10 years for least developed countries, or LDCs). Starting in 2025, tariffs on an additional 7 percent of tariff lines will be eliminated over a five-year period (eight years for LDCs). Up to 3 percent of tariff lines that account for no more than 10 percent of intra-Africa imports could be excluded from liberalization by the end of 2030 (2033 for LDCs).

- Nontariff barriers on both goods and services are reduced on a most-favored nation (MFN) basis. It is assumed that 50 percent of NTBs can be addressed with policy changes within the context of AfCFTA-with a cap of 50 percentage points. It is also assumed that additional reductions of NTBs on exports will be forthcoming.

- AfCFTA will be accompanied by measures that facilitate trade through implementation of a trade facilitation agreement (TFA). Estimates of the size of these trade barriers were provided by de Melo and Sorgho (2019). These are halved, although capped at 10 percentage points.

Macroeconomic Impacts of AfCFTA

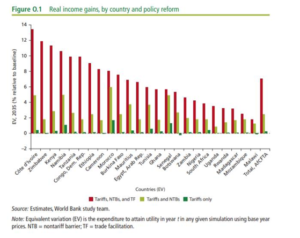

Real income gains from full implementation of AfCFTA could increase by 7 percent by 2035, or nearly US$450 billion (in 2014 prices and market exchange rates). But the aggregate numbers mask the heterogeneity of impacts across countries and sectors. At the very high end are Cote d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe with income gains of 14 percent each (figure O.1). At the low end, a few countries would see real income gains of around 2 percent-including Madagascar, Malawi, and Mozambique. Real income gains from tariff liberalization alone are small, about 0.2 percent at the continental level, although some countries would record gains of more than 1 percent. Constraints to African trade are largely attributable to the high costs of that trade. As a result, the biggest gains would come from the reduction in NTBs and implementation of the TFA. Under combined tariff liberalization and reduction in NTBs, the real income gain would amount to 2.4 percent in 2035 at the continental level. The biggest boost would arise from implementation of the TFA, which would raise the gains for AfCFTA members to 7 percent of income.

AfCFTA would significantly boost African trade, particularly intraregional trade in manufacturing. The volume of total exports would increase by almost 29 percent by 2035 relative to the baseline. Intra-continental exports would increase by over 81 percent, while exports to non-African countries would rise by 19 percent. Intra-AfCFTA exports to AfCFTA partners would rise especially fast for Cameroon, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Ghana, Morocco, and Tunisia, with exports doubling or tripling with respect to the baseline. Under the AfCFTA scenario, manufacturing exports would gain the most, 62 percent overall, with intra-Africa trade increasing by 110 percent and exports to the rest of the world rising by 46 percent. Smaller gains would be observed in agriculture-49 percent for intra-Africa trade and 10 percent for extra-Africa trade. The gains in the services trade are more modest-about 4 percent overall and 14 percent within Africa.

The AfCFTA agreement would also boost regional output and productivity and lead to a reallocation of resources across sectors and countries. By 2035, total production of the continent would be almost US$212 billion higher than the baseline. Output would increase the most in natural resources and services (1.7 percent), with manufacturing seeing a 1.2 percent rise. But output in agriculture would contract 0.5 percent (relative to the baseline in 2035) at the continental level. In absolute terms, most of the gains would be realized by the services sector (US$147 billion), with smaller gains in manufacturing (US$56 billion) and natural resources (US$17 billion). By 2035, agricultural output would decline by US$8 billion relative to the baseline. As compared with the baseline in 2035, agriculture is growing faster in all parts of Africa except for North Africa, which under AfCFTA is shifting toward manufacturing and services.

The aggregate numbers, however, mask the heterogeneity of impacts across countries and sectors. Ninety percent of countries would see their volume of services grow under AfCFTA, reflecting in part the higher demand for services as Africa’s economy grows. Similarly, 60 percent of countries would see growth in the value of their output of agricultural and manufacturing goods.

AfCFTA’s short-term impact on tax revenues is small for most countries. Tariff revenues would decline by less than 1.5 percent for 49 out of 54 countries. Total tax revenues would decline by less than 0.3 percent in 50 out of 54 countries. Two factors help explain these small revenue impacts. First, only a small share of tariff revenues come from imports from African countries (less than 10 percent on average). Second, exclusion lists can shield most tariff revenues from liberalization because these revenues are highly concentrated in a few tariff lines (1 percent of tariff lines account for more than three-quarters of tariff revenues in almost all African countries). In the medium to long run, tariff revenues would grow by 3 percent by 2035 relative to the baseline as imports rise and as tariff liberalization is accompanied by a reduction in NTBs and implementation of trade facilitation measures.

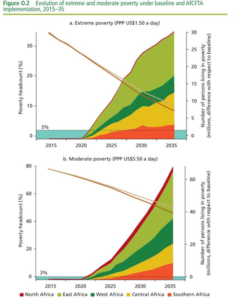

Distributional Impacts of AfCFTA on Poverty and Employment

AfCFTA can lift an additional 30 million people from extreme poverty (1.5 percent of the continent’s population) and 68 million people from moderate poverty (figure O.2). In 2015, the latest year for which detailed World Bank estimates are available, 415 million people in Africa lived in extreme poverty (at US$1.90 a day in purchasing power parity, PPP, terms). Across the continent, however, poverty rates vary widely by region-for example, from 41.1 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa to less than 3 percent in North Africa. By country, the poverty rate is 77.7 percent in the Central African Republic, but just 0.4 percent in Algeria and Egypt. Under baseline simulations, the headcount ratio of extreme poverty in Africa is projected to decline to 10.9 percent by 2035 from 34.7 percent in the latest estimate (2015). Full implementation of AfCFTA would contribute to a further decline by lifting an additional 30 million from extreme poverty. In West Africa, the poverty headcount would decline by 12 million people, while the decline for Central and East Africa would be 9.3 million and 4.8 million, respectively. At the moderate poverty line of PPP US$5.50 a day, AfCFTA has the potential to lift 67.9 million people, or 3.6 percent of the continent’s population, out of poverty by 2035.

Implementation of AfCFTA would increase employment opportunities and wages for unskilled workers and help to close the gender wage gap. The continent would see a net increase in the proportion of workers in energy-intensive manufacturing. Agricultural employment would increase in 60 percent of countries, and wages for unskilled labor would grow faster where there is an expansion in agricultural employment. By 2035, wages for unskilled labor would be 10.3 percent higher than the baseline; the increase for skilled workers would be 9.8 percent. Wages would grow slightly faster for women than for men as output expands in key female labor–intensive industries. By 2035, wages for women would increase 10.5 percent with respect to the baseline, compared with 9.9 percent for men.

Labor market results would vary by country, and some workers would lose jobs even as others gain new job opportunities and higher wages. Governments will need to focus on facilitating a smooth and inclusive transition by supporting flexible labor markets, improving connectivity within countries, and maintaining sound macroeconomic policies and a business environment that is friendly to domestic and foreign investors. Policy makers will need to carefully monitor AfCFTA’s distributional impacts-across sectors and countries, on skilled and unskilled workers, and on female and male workers. Doing so will enable them to design policies to reduce the costs of job switching and provide effective safety nets where they are needed most.

The African Continental Free Trade Area Is A Key To Help Africa Address The Challenges of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a toll on human life and brought major disruption to economic activity across the world. Despite arriving later in Sub-Saharan Africa, the virus has spread rapidly across the continent. Economic growth in the region is projected to decline from 2.4 percent in 2019 to −2.1 percent to −5.1 percent in 2020, the first recession in the past quarter century (World Bank 2020). It will cost the region between US$37 billion and US$79 billion in terms of output losses for 2020. The downward growth revision in 2020 reflects the macroeconomic risks arising from the sharp decline in output growth among the region’s key trading partners, the fall in commodity prices, and the reduced tourism, as well as the effects of measures to contain the pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis is also contributing to increased food insecurity as currencies are weakening and prices of staple foods are rising in many parts of the region.

Policy responses that result in sub-regional trade blockages will increase transaction costs and lead to even larger welfare losses. In Sub-Saharan Africa, these policies will disproportionately impact household welfare as a result of price increases and supply shortages. Welfare losses would amount to 14 percent relative to the no-COVID scenario if countries were to close their borders to trade (World Bank 2020). Border closings have disproportionally affected the poor, particularly small-scale cross-border traders, agricultural workers, and unskilled workers in the informal sector. The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the deficiencies in trade facilitation and border management procedures, as many of these countries have struggled with efforts to keep trade moving while increasing imports of essential supplies and mitigating the spread of the disease.

In this context, a successful implementation of AfCFTA would be crucial. In the short term, the agreement would help cushion the negative effects of COVID-19 on economic growth by supporting regional trade and value chains through the reduction of trade costs. In the longer term, AfCFTA would allow countries to anchor expectations by providing a path for integration and growth-enhancing reforms. Furthermore, the pandemic has demonstrated the need for increased cooperation among trading partners. By replacing the patchwork of regional agreements, streamlining border procedures, and prioritizing trade reforms, AfCFTA could help countries increase their resiliency in the face of future economic shocks.

Caveats

This analysis comes with several caveats. On the one hand, the results may underestimate the impacts of AfCFTA because they do not capture (1) informal trade flows or new trade flows in sectors and countries that are not trading in the baseline; (2) dynamic gains from trade (such as productivity increases, economies of scale, and learning by doing); and (3) foreign direct investment (FDI)-improving market conditions, competitiveness, and business sentiment will likely stimulate FDI in Africa, thereby leading to higher investment and accelerating imports of higher-technology intermediate and capital goods and improved management practices. Therefore, FDI inflows could boost regional income well above the gains predicted in this analysis. On the other hand, the results may overestimate the impacts of AfCFTA because the analysis does not capture (1) the costs of lowering nontariff barriers and trade facilitation measures; and (2) the transitional costs associated with trade-related structural change such as employment shifts and potentially stranded assets such as capital. Furthermore, the results are based on a new data set on gender-disaggregated employment and wages, which requires further vetting by country experts.

AfCFTA offers big opportunities for development in Africa, but implementation will be a significant challenge. This analysis identifies key priorities for African policy makers. Lowering and eliminating tariffs will be the relatively easy part-even if it comes, in some cases, with the challenge of how to replace tariff revenues. The hard part will be enacting the nontariff and trade facilitation measures. Such measures will require substantial policy reforms at the national level, indicating a long road ahead.