Crude prices jumped on Wednesday after the European Union proposed a ban on oil imports from Russia and also proposed removing the country’s biggest bank, Sberbank, from the SWIFT international payments network as part of a new round of sanctions targeting the country.

Details of the new sanctions are still being hammered out, but have already run into stiff opposition from Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, which is seeking a longer transitional period.

The rise in oil and gas prices triggered by the Ukraine conflict has raised the threat of the worst stagflationary shock to hit Europe since the 1970s.

A cross-section of experts has warned that Europe will be plunged into a deep recession if the region rapidly cuts off Russian oil and gas. The EU has laid out plans to lower its dependence on Russian gas by two-thirds before the end of this year and end imports completely by 2030. The euro area generates a quarter of its energy from natural gas, with Russia accounting for around one-third of the bloc’s imports. Goldman Sachs has warned that any further gas import disruptions could have significant knock-on effects on eurozone economic output and inflation.

Ironically, Moscow might come out unscathed, at least in the short-term: Norwegian energy consultant Rystad Energy estimates that Russia will collect more than $180 billion in energy tax revenues this year, good for a hefty 45% Y/Y increase despite exporting significantly less thanks to a 40% surge on oil prices.

Unfortunately, it’s poorer regions such as the African continent that are likely to bear the full brunt of the war in Ukraine.

A new report by the International Monetary Fund says sub-Saharan African countries are already facing another severe and exogenous shock, thanks to skyrocketing food, fuel, and commodity prices.

For decades, Sub-Saharan Africa has faced chronic food and energy insecurity, with the Ukraine war now about to turn the situation into a full-blown crisis.

Severe Economic Shocks

According to the IMF, food accounts for about 40% of consumer spending in the region, much higher than 17% of consumer spending in advanced economies, with ~85% of the region’s wheat supplies imported. Although this region is highly import-dependent on wheat, the grain constitutes only a minor share of the total caloric needs.

Source: IMF.Org

There’s another far more insidious catalyst that’s fueling high food prices and engendering food insecurity in Africa: soaring fertilizer prices.

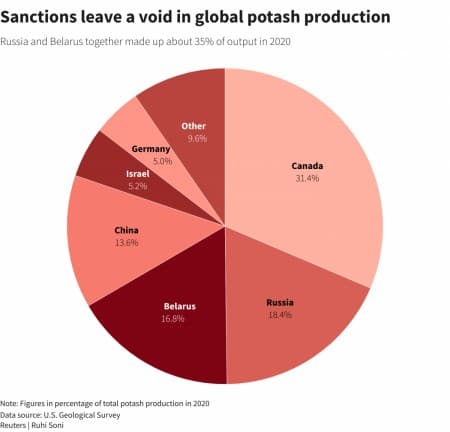

Sanctions on Russia and Belarus, the world’s #2 and #3 producers of potash, have sent prices of the key fertilizer nutrient to levels last seen during the 2008 food crisis. Prices of potash were already soaring last year on tight supplies after international sanctions on Belarus’ state-owned producer Belaruskali in response to President Alexander Lukashenko’s crackdown against political opponents.Related: The U.S. Shale Patch Is Facing A Plethora Of Problems

However, events in Ukraine have pushed prices to new highs as Russia is one of the top suppliers of potash and other crop nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphate, urea, and ammonia.

Source: Reuters

According to the International Fertilizer Development Center, a food security non-profit group, falling fertilizer use in Africa will shrink this year’s rice and corn harvest by a third.

In even the least-disruptive scenario, soaring prices for synthetic nutrients will result in lower crop yields and higher grocery-store prices for everything from milk to beef to packaged foods for months or even years to come across the developed world. For developing economies already facing high levels of food insecurity, lower fertilizer use risks making malnutrition far worse, increasing political unrest and, ultimately, the otherwise avoidable loss of human life.

But it’s not just soaring food prices that sub-Saharan Africa has to contend with.

The IMF has warned that higher oil prices will boost the import bill for the region’s oil importers by about $19 billion, worsening trade imbalances and raising transport and other related consumer costs. Oil-importing fragile states are expected to be hit hardest, with fiscal balances expected to deteriorate by around 0.8 percent of gross domestic product compared to the October 2021 forecast–twice that of other oil-importing countries.

On a brighter note, the region’s eight petroleum exporters are expected to benefit from higher crude prices.

Overall, higher fuel and fertilizer prices are very likely to negatively affect domestic food production and disproportionately hurt the poor, especially in urban areas by increasing food insecurity.

Africa To Europe’s Rescue

Ironically, Africa might be the answer to Europe’s energy crisis.

Vijaya Ramachandran, director for energy and development at the Breakthrough Institute, Berlin, says Europe should look to Africa if it’s serious about achieving energy security. Ramachandran notes that the continent is endowed with substantial natural gas production, reserves, and new discoveries in the process of being tapped. Very little of Africa’s gas has been exploited, either for domestic consumption or export.

Algeria is already an established major gas producer with substantial untapped reserves and is connected to Spain with several undersea pipelines. Germany and the EU are already working to expand pipeline capacity connecting Spain with France, from where more Algerian gas could flow to Germany and elsewhere. Libyan gas fields are connected by pipeline to Italy. In both Algeria and Libya, Europe should urgently help tap new fields and increase gas production. New pipelines under discussion currently focus on the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline Project, which would bring gas from Israel’s offshore gas fields to Europe.

But the biggest African sources lie south of the Sahara–including Nigeria, which has about a third of the continent’s reserves, and Tanzania. Senegal has recently discovered major offshore fields.

Ramachandra says Germany should not ignore these opportunities. For instance, the proposed Trans-Saharan pipeline will bring gas from Nigeria to Algeria via Niger. If the project is completed, the new pipeline will connect to the existing Trans-Mediterranean, Maghreb-Europe, Medgaz, and Galsi pipelines that supply Europe from transmission hubs on Algeria’s Mediterranean coast. The Trans-Saharan pipeline would be more than 2,500 miles long and could supply as much as 30 billion cubic meters of Nigerian gas to Europe per year–equivalent to about two-thirds of Germany’s 2021 imports from Russia (For comparison purposes, the Yamal-Europe pipeline, one of the major routes for Russian gas to Europe, is 2,607-mile-long). On its part, Nigeria is enthusiastic about exporting some of its 200 trillion-cubic-foot reserves of gas, with Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo arguing in favor of natural gas’ critical role, both as a relatively clean transition fuel and as a driver of economic development and foreign exchange earner.

Unfortunately, the Trans-Saharan pipeline will likely take a decade or more to complete, and LNG shipments to Germany would bring quicker relief.