Introduction

The first call on Government of Ghana to go to Parliament was in an article “Reading IMF Between the Lines”, after the IMF Board’s Statement on the 2019 Article IV consultations. It called for the correction of parallel numbers on the economy, as presented in the 2020 Budget and what GOG authorized for the Board—while the House was debating the Budget.

The second was when President Akuffo-Addo directed payments to depositors affected by the banking crisis. This seemed ultra vires since the 2020 Budget has no provision to pay such substantial bailout costs—not even as memorandum, as GOG now uses to sidestep well tested fiscal rules for exceptional expenses. Without heeding the call, the Receiver has started cash payments and bond issuance worth about Ghc5 billion to them.

This third call relates to the proper assessment of the impact of Corona (COVID-19). The President asked MOF to set aside US$100 million (about Ghc560 million) to support the Ministry of Health and allied agencies—without a budget and, as the Minister admitted, in anticipation of IMF, World Bank and donor contributions in a Beyond Aid era.

At this juncture, a comprehensive Statement to Parliament has precedent, and is prudent and proactive, as advanced, emerging market (EM), and low-income states are doing with fiscal, monetary, and real sector measures. The process is ongoing in the US Congress and Senate.

Part I deals with the delicate fiscal situation while Part II examines missed opportunities in continuing to use the petroleum funds to build sound and sufficient fiscal buffers.

Delicate fiscal situation

If sustained, as warned, the potential impact of COVID-19 will worsen a delicate fiscal position, ironically, from managing a delicate but risky ability to set aside several fiscal rules since 2017.

- COVID-19 economic threat

As with SARS and Ebola, the economic impact of Corona worsens the direct health risks from measured and panic situations. At the outset, the immediate impact of decisive lock-down in Wuhan and some China provinces disrupted global supply chains; the current restrictions on travel and movements in countries is aggravating the deteriorating global economic activity.

Following early signs of falling global demand, OPEC’s usual attempt to control crude oil supplies to stabilize price has led to a price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia—and steep fall in prices to sub-US$30s per barrel (pbl) or below. The spread of COVID-19, state restrictions, and slowdown in economic activity have left ministries of finance and central banks scrambling for measures to minimize the damage. These include reduction in interest rates and stimulus fiscal packages for businesses, workers, and households.

The World Bank, IMF, AfDB and others have allocated significant amounts to help vulnerable states, while awaiting their inevitable revisions of growth rates and other indicators. We can confidently predict the effect on Ghana’s economy: slackened global demand leading to falling commodity prices for crude oil, cocoa, and gold. The secondary effects are low growth and shortfalls in foreign exchange and revenue flows to the Budget.

The similarities with Ebola, which COVID-19 could dwarf, include falling crude oil prices between late-2014 and end-2016 to sub-US$40 pbl, compared to US$99 pbl in the 2015 Budget. Together with experiences from the global financial crisis and BRIC meltdown, Corona warrants prompt Executive and Legislative action to clarify the economic impact.

- Tight fiscal situation and Corona

As a new oil-producing state, the point is lessons learnt beyond blaming past effects of low growth rates and higher deficits on non-performance. The continuous side-stepping of fiscal rules in the 2020 Budget and non-adherence to the oil-based fiscal buffers since 2017 make it difficult to adjust to the ongoing fiscal and economic situation.

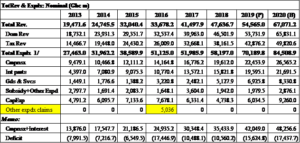

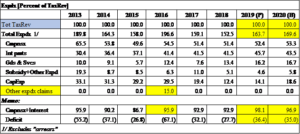

- Burden of wages and interest payments: Tables 1 and 2 show Ghana spending about 98 percent of tax revenue on these items which, as non-discretionary and statutory, leaves little room for making flexible decisions during crisis. The trends portray high wages and expensive loans, despite the good impression given in the last three (3) years.

Table 1: Revenue and expenditure: Nominal (Ghc)

Table 2: Expenditure (% of Tax Revenue)

- Fall in crude oil prices worsens fiscal situation: The main risk is sharp falls in tax revenues from the Petroleum Funds under the Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA), from the price war. Early projections suggest that the ABFA shortfall could be about Ghc 250 million and, overall, Ghc750 million, including GNPC and other funds.

- Reduction in pump prices adds to pressure: Under liberalization, GOG increases petroleum prices when crude prices rise and, hence, it responds in opposite step when prices fall. This will mean less petroleum tax revenues.

- Not prudent to keep temporary taxes: The temporary taxes (rise in corporate income tax and import duty rates), designed for austerity since the Rawlings era, lapse with positive economic change. Hence, the quadrupling of oil revenues from three (3) oil fields made this government the most fortunate to remove them in 2017. The extension that mainstreams the revenues removed a major fiscal handle in such crisis.

- Low estimates for arrears impede emergencies: A feature of budgets since 2017 is relatively low provision for annual arrears which are, curiously, spent to the pesewa. The goal of posting of impressive fiscal outturns now makes it incredible for US$100 million Corona pledge to be about 35 percent of total provision for arrears for 2020.

- Cost of Free SHS and special projects: The 2020 Budget is also unique in not disclosing the full cost and intake of large numbers of free SHS students that will enter tertiary schools this fiscal year (September 2020). This is also true of the full cost of completing many special projects in 2020.

- Higher deficit and dwindling borrowing space: These factors will result in a higher deficit and financing through loans or grants—which defeats the “Ghana Beyond Aid” stance. However, with high interest costs and public debt at 63 percent of GDP—before the first 2020 Sovereign, bailout, and other bonds—the borrowing space is also closing.

The 2020 Budget gives a deceptively positive fiscal view by excluding offsets (Table 1: isolated Ghc5,035 million or 15 percent) and exceptional expenditures (e.g., bailout costs and energy arrears). The IMF (next section) shows a better pre-Corona view and explains why making further adjustments could be difficult.

- Adjusted IMF fiscal or budget deficit and public debt numbers

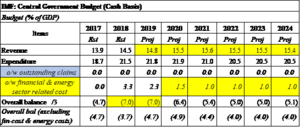

A reality check is the fiscal outlook from the IMF Board, which is worse than the 2020 Budget position. Table 3 shows differences in the deficit and public debt, which the Fund back-dates for 2017 to 2019 and elevates for 2020 and medium term.

Table 3: Central Government Budget (Cash Basis)

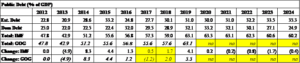

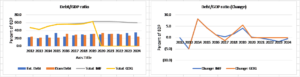

Table 4 and Figure 1 also show the IMF positions on public debt, which is worse than the disclosures in the 2020 Budget and recent State of the Nation Address (SONA).

Table 4: Debt-to-GDP ratio (Domestic, External & Total)

Figure 1: Debt-to-GDP ratio: (a) total and (b) change)

The following points from the tables and graphs stress the need to clarify the fiscal performance and outlook.

- IMF retroactively adjusts the budget deficits (2018 and 2019) to 7.0 percent, compared to GOG’s 3.7 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively.

- The pre-Corona deficit of 6.4 percent for 2020 (compared to GOG’s 4.7 percent) is higher than the end-2016 deficit of 6.3 percent.

- The Fund gives multi-year (2020 to 2024) commitments for bailout and energy sector costs, of about 1 percent of GDP, that is not in the 2020 Budget.

- It elevated the debt-to-GDP ratio to 63 percent before MOF and BOG did officially.

GOG must bridge the gaps with IMF, as it always does in Article IV or Program contexts, notably for bailout costs and energy arrears of approximately 1.5 percent in 2020 and 1 percent of GDP from 2020 to 2024.

Conclusion

The analyses point to inevitable higher deficit and borrowing, originally due to preference for consumption overt borrowing to support expensive and indiscriminate social intervention programs. Even rich states “target” such programs for low-income persons mainly, as the current Minister intimated against the wrath of hardliners. Former President Mahama’s call for a national dialogue on key programs is worth considering as likely motivated by the nation’s (single spine) wage overrun experience.

While popular now, the path to unsustainable use of virtually all resources and, gradually, loans for consumption is disastrous. Successful nations call on their citizens to work hard, be innovative, and sacrifice—with their rich and middle-class, particularly, understanding that they cannot be part of all state largesse. Indeed, their tax and expenditure policies require that they shoulder part of the burden of nation-building on behalf of low-income compatriots.